What's My Name? (Sermon on Judges 12:5-6)

On Sunday, November 9, 2025, I gave a sermon at Shalom Community Church. This is an adaptation of the sermon. Here is an audio version.

Scripture

Judges 12: 5-6 (The Inclusive Bible)

[5] The Gileadites overran the fords of the Jordan near Ephraim. When the fleeing Ephraimites asked permission to cross over, the Gileadites would ask, “Are you an Ephraimite?” Whoever answered “no” [6] was asked to pronounce the words “shibboleth.” Anyone who mispronounced the word as “sibboleth” was seized and killed at the fords of the Jordan. And 42,000 Ephraimites were put to death at the time.

Reflection

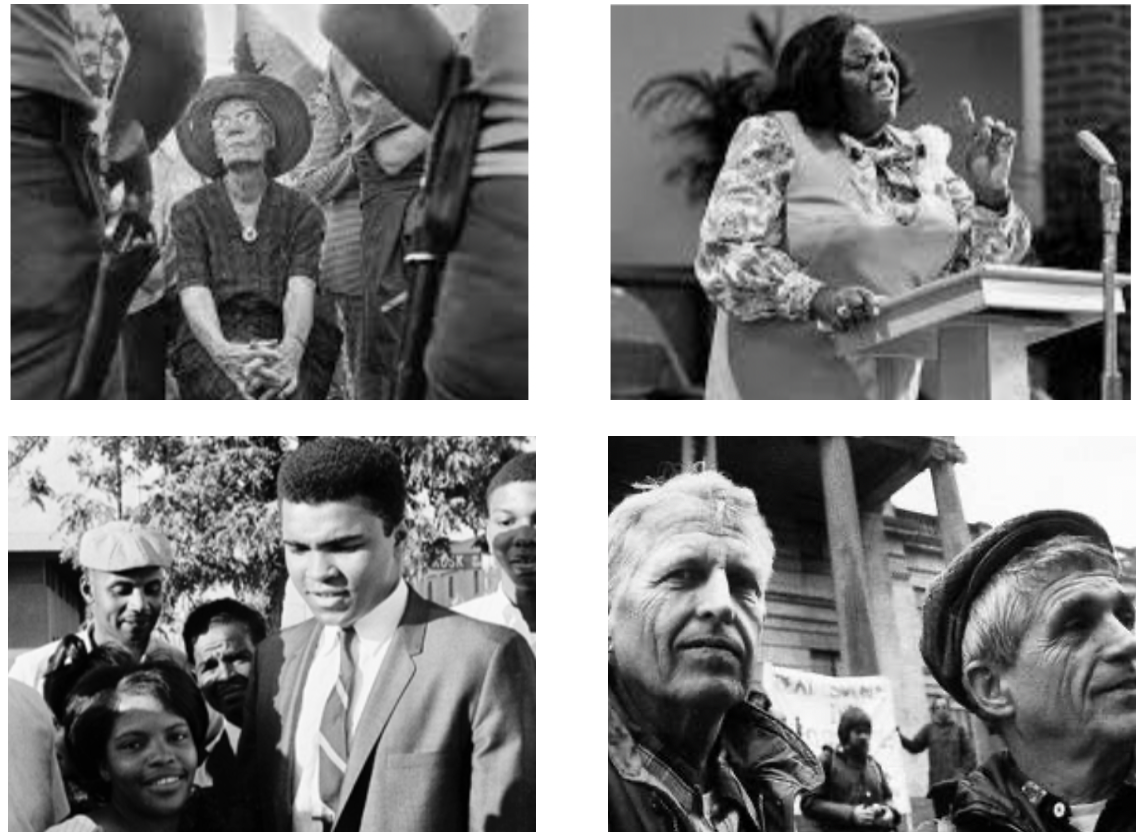

I want to start with a secret. Clay–you know, that Clay–is named, in part, after Cassius Clay. Yes, that one: Muhammad Ali, the boxer and social activist.

And, yes, Muhammad Ali was amazing in the ring. BUT, that’s not what I want to talk about today. Outside xthe ring, beyond the cultural icon even, Ali was a man–a complicated one1–who wasn’t afraid to break the rules:

- He joined the Nation of Islam, for example–which yes, has a complex history. But it led him to speak out FEARLESSLY for Black empowerment, even when it was really DANGEROUS to do so.

- He also refused the draft for the Vietnam War because he believed it was wrong, even though it came at great personal cost.

Later, he became a humanitarian, an ambassador for peace, even lived for a while right here in Michigan.2 He had a daughter named Laila (another reason I like him) and he suffered, publicly, from Parkinson’s Disease.

(However you remember him, he’d want you to remember him as “the Greatest.”)

Clay Who?

But Muhammad Ali wasn’t born Muhammad Ali. He was born in 1942 in Kentucky–in the Jim Crow South–as Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr. He was named after his father (Clay Sr.), who was, in turn, named after a white Cassius Marcellus Clay, a “fiery,” 19th-century slave-owner-turned-abolitionist–also from the South–who survived assassination attempts–twice!–due to his anti-slavery beliefs and often controversial activism.3

That Clay–the white one–was actually a contemporary of Ali’s great-great-great-grandfather, Alexander Archer. Archer was born enslaved, but escaped captivity twice and eventually became THE LITERAL MODEL for the Emancipation Memorial in Washington D.C. At one point, he was sold off for being “too uppish,” which, knowing Ali, makes it seem like this kind of proto-Black Excellence must have run in the family.

There have been a lot of pretty remarkable Clays here in the United States–and maybe our Clay will be one too. But we can also see that by the time this particular Clay came along, he was already part of this long trajectory of both abolition and the struggle for Black identity–a legacy he didn’t just inherit, but carried forward. With style, and personality.

Becoming محمد علي

Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali, as an adult, changing his name after converting to Islam and joining the Nation of Islam–a religious and Black nationalist movement founded just up the road in Detroit. He’d first learned about them at an amateur boxing tournament in Chicago in 1959, and got hooked after seeing a cartoon in one of their newspapers depicting the forced Christianization of Black people.

He soon found mentors in Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad, the group’s leader. He started attending meetings, quietly at first, but then one thing led to another so that after defeating Sonny Liston for the heavyweight title in 1964, Ali publicly announced that he’d converted and changed his name.

Cassius Clay had always adored his name, saying “it was the prettiest name he had ever heard, perfect for the prettiest and greatest heavyweight champion of all time.”4 But he was learning that somewhere along the line his family had been stripped of their ancestral name, and Ali came to view “Clay” (and he’d probably think of “Archer” the same way) as a “slave name.”

And so, he gave it up.

He initially used the name Cassius X–that was common, just like Malcolm Little (Malcolm X) had done–but later adopted “محمد” (which means worthy of praise) and “علي” (which means lofty).

The name change was a significant part of Ali’s spiritual journey (and, in fact, the spiritual journeys of many people who convert to other religions. [we sang that hymn popularized by Cat Stevens today–but that’s his stage name. His real name now is Yusef Islam.]) For Ali, and others like him, it was a way to reclaim an identity rooted in African (and Islamic) history–not the history of slavery–and it was a powerful assertion of his new identity as a Black man AND a Muslim.5

And, naturally, it was controversial.

Sibboleth I MEAN SHIBBOLETH

The language we use–sometimes a name, even a single word–can divide us. And the story we read today from Judges about a “shibboleth” is a good example of that. “Shibboleth” is an ancient Hebrew term that originally meant “a torrent of water,”6 but now it’s also a loan word in modern English that means–because of this story–“any… choice of phrasing or single word–that distinguishes one group of people from another.”7

In this section of Judges, Jephthah was the judge, the charismatic leader. (He’s also the guy who, BTW, would go on to sacrifice his unnamed daughter because of a rash vow he’d made8–and unlike with Isaac, God did not come to her rescue. Which is just to say that sometimes there’s really nothing to learn from the Bible, except “repent, repent.”9)

After Gilead defeated the invading tribe of Ephraimites, they trapped those who were trying to escape by securing the Jordan River’s fords–the only places you could cross because the river was… a giant torrent of water. To identify (and kill) these Ephraimites, they told each suspected survivor to pronounce shibboleth. The Ephraimites had an accent–they got it wrong–and the rest is history. It was kind of like the first password in Western literature.

And today, “shibboleth” maintains that same meaning. Think “soda” vs. “pop.” Or “Major” vs. “Meijer.” Or “roof” instead of “ruf,” which are all–admittedly low stakes–ways that people figured out that Ashley and I were not from around here.

But there are higher stakes examples too, particularly in conflicts, particularly when the two sides look alike. Shibboleths were used with:

- Koreans and Japanese during the Kantō Massacre (jūgoen gojissen);

- with Germans and Dutch during WWII (Scheveningen);

- in the Derry/Londonderry debate during the Troubles in Northern Ireland; and

- it is happening with Russians and Ukrainians today (palianytsia).10

Everywhere, in every time, shibboleths shape who belongs.

“Muhammad Ali” as Shibboleth

In the same way, Cassius Clay SLASH Muhammad Ali became its own kind of shibboleth. It was like a test: if you used the name Muhammad Ali, you accepted and respected his new identity. If you kept calling him Cassius Clay, you didn’t. I think it would be like deadnaming non-binary person today.

The most famous example of this “test” came in the lead-up to Ali’s fight with Ernie Terrell in 1967, during which time Terrell repeatedly–and intentionally, it seems–called Ali by his former name, even in press conferences. During their bout, Ali responded by hurting Terrell over ALL 15 rounds of the fight–some even accusing Ali of purposefully dragging it to make his point. With every punch, Ali would shout a question: “What’s my name?” It was a vicious and highly public lesson–not the kind I think any of us should emulate–but Ali was making it clear: his identity was not up for debate.

Beyond the fight,11 it became a test for the media and the wider public, too. For years, many white-dominated newspapers, including The New York Times, refused to call him Muhammad Ali. (Some Anabaptists did, too! It’s an irony of history that Muhammad Ali, a conscientious objector, ANNOYED those with dearly held peace beliefs as much as he did the rest of White America precisely because he had somehow made a minority position “popular.”1213)

Some news outlets claimed they HAD to use “Cassius Clay” because of legalistic policies, but everybody knew what was going on. Clinging to his old name was a passive-aggressive signal of their disapproval of his religion and outspoken racial politics.

And it wasn’t just about Ali. The whole thing pointed to a larger power struggle that was going on in the United States at the time: Where you stood on Ali’s name often revealed where you stood on the Civil Rights movement and on the more radical politics of people like Malcolm X, Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam.

When to Break the Rules

And then Muhammad Ali broke a rule. A big one, a federal law. Rooted in his religious beliefs and moral conviction, he refused induction into the U.S. military for the Vietnam War.

Lots of people–some of them in our own families–didn’t want to get drafted, and avoided it one way or another. But Ali didn’t have many options. He wasn’t in college, so no deferment. He was in great shape, so a medical exemption was out. And–he said this and I believe it–was Absolutely American;14 he wasn’t about to leave the country he loved to immigrate to another.

At first, Ali didn’t even qualify for the draft. He’d taken an aptitude test, and because of his dyslexia, had scored too low. He joked: “I said I was the greatest. Not the smartest.” But then the Vietnam War dragged on, and it killed a lot of people. We needed more soldiers, and the military lowered their standards. And suddenly, he was eligible.

Ali tried to claim conscientious objector status, which was granted to Quakers, Mennonites, and other pacifist groups. But a local draft board saw his stance as political rather than religious, even though a hearing officer found his beliefs sincere. Simply put, the Nation of Islam was not considered a religion and certainly not a peaceful one by the U.S. Government. (Is it a religion or a Black nationalist movement? It’s a Shibboleth.15)

Regardless, there was intense pressure from the government, the military, even the general public to make an example of Ali. There have always been rules about who belongs in America… going all the way back to Alexander Archer, and beyond. From slavery, to unequal citizenship, to segregation, to mass incarceration and the War on Drugs16–there’s always a boundary, always a limit… if you’re Black.17 And those goalposts are ALWAYS moving; Ali got caught up in the middle of the white establishment’s latest attempt to adapt those rules to the new realities of the Civil Rights Movement and an increasingly unpopular war.

And so, when the time came, he just refused.

Activists and supporters cheered his moral stand against the Vietnam War and racial injustice, while critics condemned him as unpatriotic. It was a watershed moment–Ali was immediately arrested and later convicted of draft evasion, and faced the possibility of a fine and years in prison. He was forced to forfeit his heavyweight title and lost his boxing license, banned from the sport during what would probably have been the three and a half PRIME years of his career. While the Supreme Court would ultimately overturn his conviction, in the meantime he faced real financial struggles. And over time he also lost his legendary speed and reflexes so that when he finally did return, he never “floated like a butterfly” again.18

I See Words19

The point is this: it’s not the words “Muhammad” or “Ali” or “Cassius” or “Clay.”20 It’s the real people-and their real stories–that they signify. Naming is a kind of power,21 and in the same way that we get to decide whose names matter (and which ones we’ll use), we also decide who gets to belong, who gets to speak, and who gets left out. Shibboleths, then, are ultimately about rules, and who gets to make them. And whether 3,000 years ago or 50 years ago or today, these “rules”–explicit and implicit–are made by those in power.

–

I think y’all already know this about me: I am a rule follower. I also come from a place of privilege, so my default when I encounter an unjust rule–and I do–is to try to change it, from within.22 But like Ali sometimes you just have to break the rule.

And it’s because rules aren’t only about what’s allowed, or not allowed–and who gets to say so–they are also about who gets to break them. And I’m speaking here from experience: As someone who often benefits from these systems, these rules, I know–often instinctively–when it’s safe to bend, or even break them.

In my work as an archivist, for example, we pride ourselves on knowing the rules–or “standards.” Sometimes we even helped write them. But we also know that archives are a fundamentally colonial enterprise: what ends up in our collections inevitably reflects choices WE MADE about whose voices are preserved and whose stories are left out. And so–recognizing that we got that wrong sometimes–we’re also happy to break those rules, especially when it expands access to our collections or repairs relationships with those communities we’ve historically left out.

And that’s maybe an example of rule breaking, “for good.”23 But we all know there’s a darker side, too. One I’ve seen personally, although on blessedly few occasions. All you have to do is get a group of white men, even the progressive kind, behind closed doors. And it’s an open secret that the rules they follow in public go out the door real quick.

When Ali broke his rule, though, it wasn’t because he was entitled, or it was safe. He couldn’t lean into privilege–for good or bad. It was not for the sake of rebellion, but because he thought it was the right thing to do, and because it reflected his deep faithfulness to God’s justice. To do what Rachel talked about: to uphold human dignity, promote repair and healing, protect the vulnerable and make space for the marginalized.

The Secret, REDUX

But I said all this was a “secret.” Not like a secret secret, just not information I’ve necessarily volunteered. I feel… tender… telling ya’ll that Clay is named after that Clay, especially here in Ann Arbor–it’s kind of a bubble–and especially since we go to a peace church. Ali was a BOXER, and as a boxer he practiced violence–a very gendered, masculine kind of violence.24 A kind of violence that showed up in his personal life too.

I also feel tender sharing this with my family. I grew up in a military town–home of the largest military base in the United States–during the 9/11 era, no less. And my grandfather fought in the Vietnam War. For much of my life, “patriotism” meant something very different for me than it does today.

And, yes, here I am, lifting up a Muslim today–one who eventually converted to a more orthodox form of Islam–even though we’re gathered here for a Christian service. Ali’s story is different from my own, it complicates my own. But I hope in sharing it that I’m telling a truth.

Land the Plane

The only time I ever saw Muhammad Ali live was on TV, when he lit the torch at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta. By then, Parkinson’s had taken its toll; his hand shook, his face was still, even unemotional. When he got up to the podium and tried to light the cauldron, for a moment it looked like it wouldn’t work. That would have been its own kind of symbol. But finally, it did. I remember that moment because it was one of the first times I’d ever seen someone like him who refused to hide the things that others might have wanted him to.25

When Ali died on June 3, 2016, some said that he had “transcended” race… But that’s not true. “Race was the theme of Ali’s life. He insisted that Americans come to grips with a Black man who wasn’t afraid to speak out, who refused to be what others expected him to be. He didn’t overcome race… [or] racism… He called it out.”26

Shibboleths aren’t just ancient history; they’re all around us. They draw lines, split us apart, and force us to take sides–even if we wish we lived in a world where we didn’t have to. As people of faith, though, sometimes our calling is exactly that: to take a side, to break a rule, and to push back against what the dominant culture expects of us.

God invites us, I think, to position ourselves like Ali:

- whose historical, lived experience–all the way back to his great-great-great grandfather–kept his eyes open to injustice and led him to an orientation toward the underside27;

- to remain attuned to those sacred moments when not following the rules is the most faithful thing we can do; and sometimes, even when we like quiet integrity,

- to be loud and outspoken, calling out, naming racism (or sexism or anything else) when we see them–especially when the rules say they’re allowed.

(And yes, we have to be peacemakers, even if we also like to watch boxing sometimes… or do martial arts… or, you know, did that demonstration in church that one time.)

In the end, Muhammad Ali is a figure I think we should all wrestle with–with honesty, and with conviction. May we be the kind of people who respond when a living God meets us–not only in familiar stories–but also in the lives of those who challenge us: a Black Man and a Muslim like Ali.

Amen.

Notes

Categories: talks

-

Yeah, I know I’ll be romanticizing a bit today. (I have Dave to thank for some of that, and a visit to the Muhammad Ali Museum in Louisville, KY.) And I hope in doing so I’m not conveniently glossing over some of the more critical or controversial aspects of his life. But it’s a love letter! ↩

-

He also voted for Ronald Reagan and was into semen retention, just to keep us on our toes. ↩

-

Wikipedia, “Cassius Marcellus Clay” ↩

-

Ali: A Life by Jonathan Eig, p. 159 ↩

-

NOT a Black Muslim ↩

-

Or maybe an “ear of grain…” ↩

-

Wikipedia, “Shibboleth” ↩

-

How to Read the Bible by James Kugel, p. 408 ↩

-

Phillis Tickle, also A Year of Biblical Womanhood: How a Liberated Woman Found Herself Sitting on Her Roof, Covering Her Head, and Calling Her Husband ‘Master’ by Rachel Held Evans ↩

-

I am 99% sure I got this idea from Peter Rollins or The Fundamentalists, but for the life of me I can’t find a reference to it. ↩

-

Which, let’s be honest, probably also helped to boost ratings. ↩

-

There’s your wicked reference, Leila ↩

-

“The CO Mennonites once found objectionable” by Richard Preheim in Anabaptist World Review ↩

-

This was the book UNC Chapel Hill’s summer reading program recommended for incoming freshmen and transfer students when I was an incoming freshman. And I read it! ↩

-

Is Donald Trump a king? It’s a shibboleth. ↩

-

The New Jim Crow by Jennifer Harvey ↩

-

Same for those “merciless Indian savages” in the U.S. Constitution. Also “No better Do Better” by Supaman. ↩

-

Some of what got cut: It’s easy now to see that he was right. The Vietnam War was awful. Wars today are awful. And they beget more violence… One weekend in September we mourned mass shootings at a Mormon church here in Michigan and at a beloved watering hole–my beloved watering hole–in North Carolina. Both tragedies involved Iraq War veterans–my generation’s war. And that’s not me demonizing veterans, it’s me demonizing war and the psychological effects of war, even for the “winners.” But at the time, the dominant culture just didn’t see it that way. ↩

-

Olga, I mean Joe ↩

-

–or even “Junia” or “Junias.” (Some of you will know Junia’s story: an early Christian apostle whose name was later changed to its masculine form, Junias, by some scribe or editor along the way who simply couldn’t believe that a woman could be an apostle.) ↩

-

It’s why after tragedies, we insist on saying the victims’ names: it preserves their humanity and links individual loss to broader patterns of harm. We saw this with BLM and in Terri’s vigil for Palestinian health workers killed in Gaza. Naming is a way to drive public awareness and demand accountability. ↩

-

I’ve also learned that there are times when you really need to clarify rules you’re confused about before you accidentally break one. ↩

-

Another! ↩

-

His own daughter acknowledged it, too, that he was “a little bit of a male chauvinist.” The Nation of Islam wouldn’t even accept Ali at first, precisely because boxing was too violent. ↩

-

Maybe the things they didn’t like about themselves? Inside themselves? “Secrets” by Mary Lambert ↩

-

Ali: A Life by Jonathan Eig, p. 545 ↩

-

“The God Who Takes Sides: Why Neutrality Isn’t Biblical w/ Dr. Drew Hart” on Homebrewed Christianity w/ Dr. Tripp Fuller ↩