Not Just a Copy (Making Michigan)

On Thursday, October 17, 2024, I gave a lecture with Michelle McClellan as part of the Bentley Historical Library’s “Making Michigan” series. The video is available on YouTube.

Digitization

So, we decided to digitize this collection and put it online.

The process–because digitization is a process!–began at least conceptually in spring 2023 and in earnest in November 2024 with our first shipment out to a vendor. And it’s still ongoing! Part of the reason that projects like this take so long is, in addition to just being big, they can get kind of complicated. But, you know, that complicated bit is kind of what makes our work interesting and that’s what we wanted to share with you tonight.

The “Stuff”: It’s a Collection of Negatives

So, what actually IS digitization? I’m sure we all have an idea of what it is. From my perspective, in order to understand digitization you have to start with the stuff you’re digitizing.

The Ivory Photo photograph collection at the Bentley is, well, a collection of photographs. Over 10,000 of them. In individual sleeves and stored in boxes like these.

More specifically though, the Ivory Photo photograph collection is a collection of photographic negatives (at least 99.99% of it). And that”s a really important thing to know.

The vast majority of digitization we do at the Bentley–and that our researchers do and sometimes donors do–is relatively straightforward. (Of course, you always need that qualifier “relatively” but it is…) We’ve been doing some version of it since the advent of photocopiers and scanners, so it’s something that at this point we have a fair amount of experience with.

Digitizing photographic NEGATIVES, however, is ANYTHING BUT simple.

And that’s for at least three distinct reasons that I’ll talk about tonight, but probably a whole lot more:

- Negatives are Not Positives

- Negatives are Small. Really Small

- Some Negatives are FULL of Inherent Vice

Negatives are Not Positives

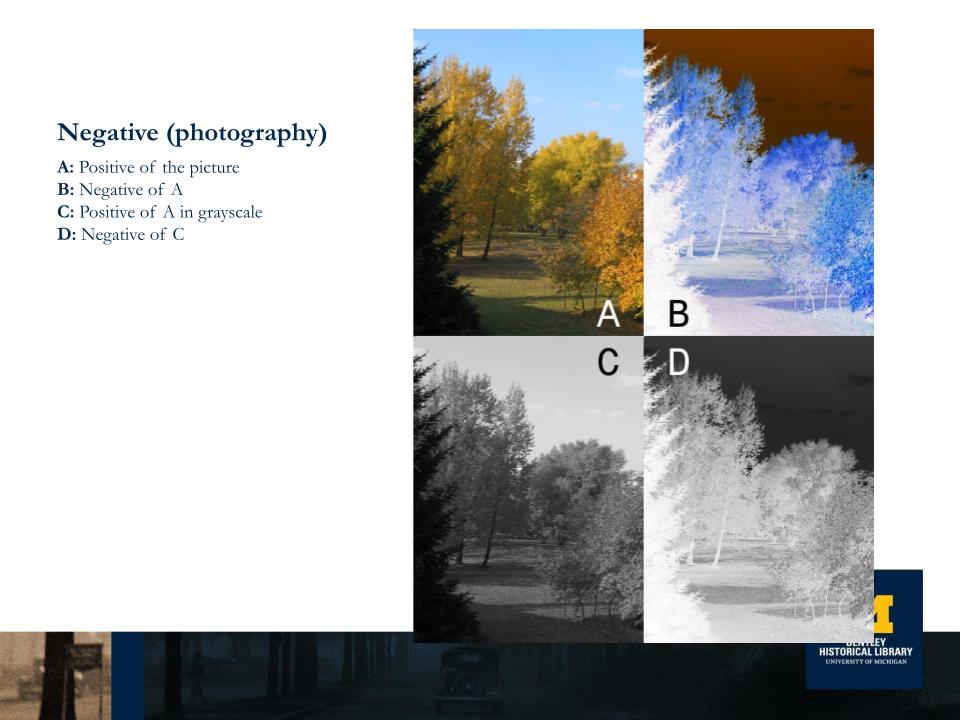

Let’s start with the obvious: negatives are not positives. In photography, a negative is a reversed image of a subject, usually on a strip of transparent plastic film–or before that, glass plates, which we also have at the Bentley–in which the lightest areas of the photographed subject appear darkest and the darkest areas appear lightest. Until the advent of digital cameras, this technology was basically all we had and negatives came straight out of the camera after you’d taken a picture or a set of pictures.

You then USE the negatives to make POSITIVE prints, physical ones, on photographic paper, and you do that by EITHER: projecting the negative onto the paper with a photographic enlarger; OR making a contact print. The paper gets darkened in proportion to its exposure to light–this is why folks who develop film work in “dark rooms”–so a second reversal ultimately results which restores light and dark to their normal order.

There’s all kinds of complicated imaging science here that frankly I’m not smart enough to get into–histograms and charts and that kind of thing for digitization that tell you which negative color equals which positive color–kind of… color is actually really difficult to quantify–how to convert from grayscale like the ones in Ivory Photo, etc.

What’s maybe NOT so obvious is that there’s a lot of CREATIVITY and ARTISTRY that goes into the development of images from negatives to positives and in fact artists take PRIDE in this. Ansel Adams famously said, “The negative is the score, and the print is the performance.” And as you can see, his prints look nothing like the straight positive from the negative. Instead, he would do a lot of analysis of the various brightness levels of a scene and use that information to anticipate and manage the way those brightness levels would be rendered in the final printing. And that’s why his final printings are so stunning.

Which is all really cool for the artists! And… not so much for the archivists. We had to come to terms pretty quickly with the fact that we’ll never know exactly what Ivory’s intent was in developing these negatives, and so we decided early on a kind of PHILOSOPHICAL APPROACH to this work, that we’d digitize the negatives AS-IS.

Now, this is a bit of an oversimplification–in reality, there’s always a bit of an art to the science of digitizing negatives, you can’t REALLY do it “as-is”–but just as these negatives capture in a very physical and literal sense a moment in time, we’re trying to capture the negatives when we digitize them as they exist in THIS moment in time without enhancing them or trying to make them pretty/aesthetically pleasing–or even trying to make them look old with sepia tones–and without researching, for example, HOW Ivory made whatever final prints he did, or even knowing what the final prints looked like (because in most instances, they don’t exist anyway).

Negatives are Small. Really Small

The second reason negatives are so hard to work with is because they’re small. I mean really small.

We’re talking 35mm in some instances, barely larger than an inch. And there are some unique challenges to digitizing something that small.

Let’s say we put one of Ivory’s negatives on a typical flatbed scanner like you might have at home or in your office, the same way you’d do an 8.5x11in piece of paper to email a PDF of it to yourself. If we did that, we would get a digital surrogate (that’s technically digitization) of the negative, BUT: 1) the quality would be terrible, because flatbed scanners aren’t usually backlit and so all you’d get is a black blob; and 2) even if we made some adjustments, the resulting image wouldn’t be all that useful. Who wants a 1:1 scale replica of a 35mm negative? The approach you’d use for scanning modern, text-based documents simply doesn’t translate well to archival digitization of photographs.

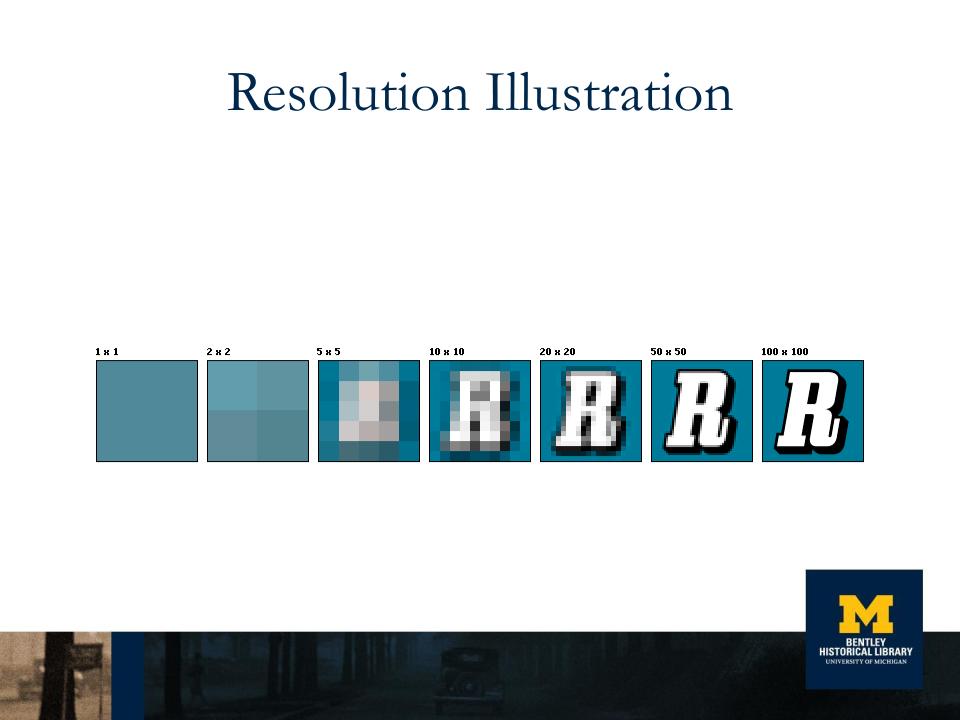

And this is where a fundamental concept in digitization called “resolution” comes into play. While it’s not the only consideration when digitizing, it is a BIG one. The RESOLUTION at which a document is scanned is a TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION, measured in dots per inch–thats DPI–or pixels per inch–PPI, that determines, among other things, how closely it can later be inspected without becoming fuzzy, and you can see some examples of that here. A higher resolution scan uses a more powerful camera and will produce a clearer image with more detail that can be viewed FROM A DISTANCE or when ZOOMED IN real close.

As our digital imaging archivist put it, “generally the smaller the image the higher the resolution you want.” And that makes sense, right? “And since these are negatives…” which are REALLY small, we wanted a REALLY HIGH resolution. A typical flatbed scanner–even though some claim falsely that they can do more–can do 300dpi for general purpose scanning; we went with 4,000dpi(!!!) for the 35mm film in this collection, actually any of the negatives up to 4x5in. And that’s because we wanted a really high quality image on the other side.

Of course, we knew scanning at such a high resolution would have some consequences. It would impact file size, for example. Higher resolution == larger files, actually about 20 TB altogether. (For reference, my phone has 64GBs of storage; that’s 312.5 of my phone!) As you might imagine, this amount of content can be more difficult and more expensive to store and share (especially compared to the physical collection which only takes up a few feet on a shelf, barely a drop in the bucket of our 90,000 linear feet of storage capacity).

We also knew it would impact the overall project timeline, because scanning at a higher resolution takes longer, especially if you’re scanning a large number of items like we were. But, even with all that, we treat this kind of digitization like we’ll only get one shot at it–and in a very few cases, this actually turned out to be true. We wanted to do it right.

This led us to a practical problem. With respect to my colleagues, the Bentley is a “general purpose” archive and if we specialize in anything, it’s probably paper (including born-digital “paper”). We certainly take in all sorts of more specialized formats, including photographs like these and legacy audiovisual formats and removable media for storing digital material, and we have amazing archivists who know how to handle that stuff, but we are BASICALLY “optimized” for office documents. This means that while we do a ton of digitization (over 60,000 images/year), we simply don’t have the specialized equipment we’d need in-house to digitize images this small at the level of detail we desired. We’d need a really powerful camera with a fancy lens to do that!

So, we knew we’d need to find a vendor to do this work. Which we eventually did: Chicago Albumen Works (in Massachusetts, of all places… and don’t ask me how the Windy City ended up in Massachusetts). This, BTW, was its own kind of adventure, one I don’t have time to talk about in much detail tonight. Suffice it to say, the world of preservation-quality digitization vendors for libraries, archives, and museums is pretty small, and the world within that world of preservation-quality vendors for photographic negatives is EVEN SMALLER.

Some Negatives are FULL of Inherent Vice

The last reason negatives are hard to work with is that SOME of them, actually a lot more than most of the other types of material in our archive, are full of what archivists call INHERENT VICE–the tendency of material to deteriorate due to the essential instability or interaction among components. You know, kind of like humans… The negatives in the Ivory Photo photograph collection are no different.

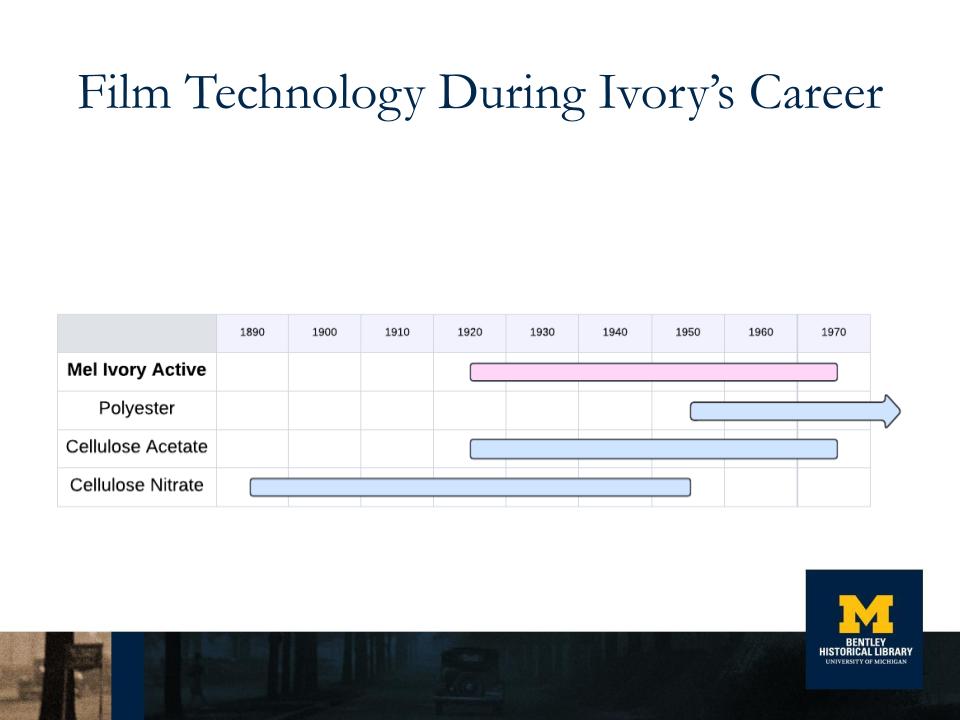

Ivory was active from the 1920s to the early 1970s, a time when photography was really changing, as well as the technology that enabled it. That’s part of what makes the collection interesting, its timespan. By the time the 70s rolled around, film was relatively stable, and thankfully most of the film we have in the collection was made on this kind of film. However, on the way there, film technology went through a couple of iterations that mean that the negatives in this collection, especially the older ones, suffer from not one but TWO different types of inherent vice because the film they’re printed on is chemically unstable, but in different ways.

Cellulose Acetate

The first concern was film made from CELLULOSE ACETATE, which causes negatives to basically disintegrate over time. This was used from about the 1920s until the 1970s. If you’ve ever smelled an old film reel and it smelled like vinegar–that’s what it smells like when you open up our cold room!–it’s because of a chemical reaction that causes the deterioration of acetate film, resulting in the film becoming brittle and shrinking and off gassing of a chemical that smells like acid, like vinegar.

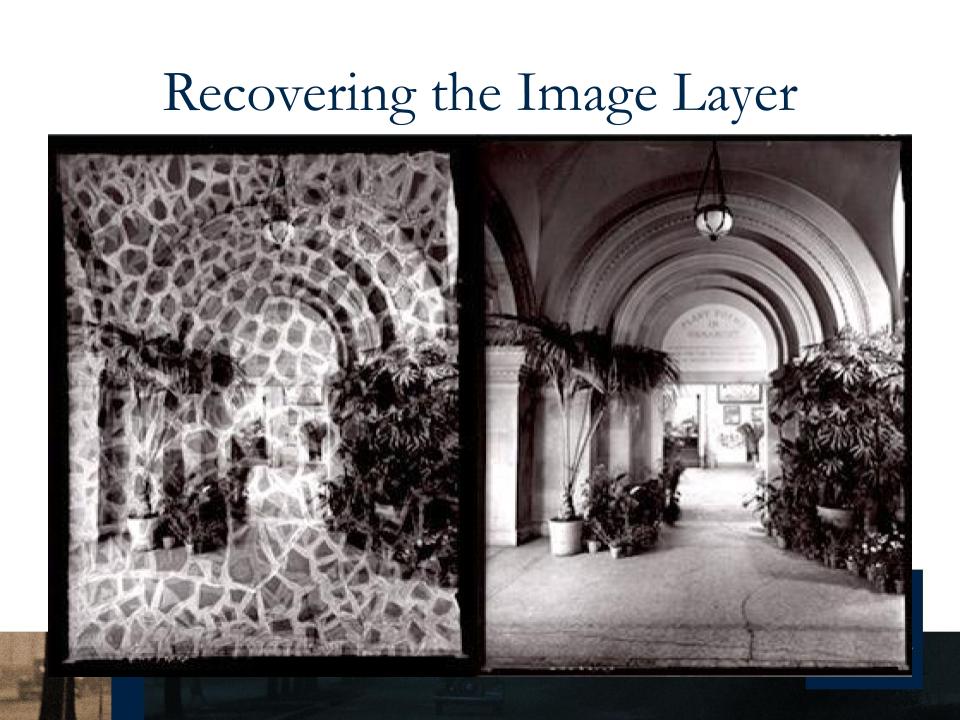

A lot of the film in our general collections is made from acetate film, and so our SOP is to keep it in cold storage to slow down the dissolving process. Even still, a few of the negatives in the Ivory Photo photographic collection were in really bad shape, and looked like this. Not usable at all.

That said, the good folks at Chicago Albumen works had a solution for this. And this is a good example of how digitization can sometimes illuminate some of the “hidden” (to the naked eye) qualities of physical material. In cases of acetate deterioration, they are able to peel the photographic emulsion and reassemble the image layer beneath it, like a jigsaw puzzle–only one that’s about the thickness of the hair–to restore the image layer of the photo.

So, something like this–and this is an example from their website, not Ivory–now looks like this. Pretty amazing, right?

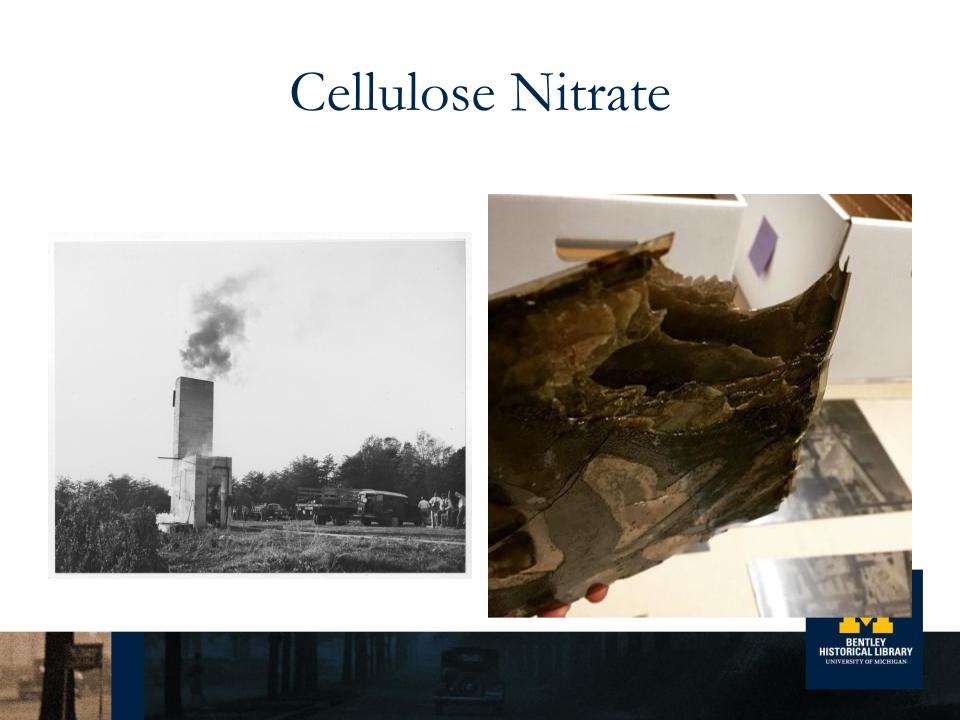

Cellulose Nitrate

The second concern was film made from CELLULOSE NITRATE.

his EVEN OLDER type of film was popular from the 1890s to about the 1950s. Not only is it unstable–it also deteriorates over time… in rather dramatic ways!–it is also considered a HAZARDOUS MATERIAL, known for catching fire spontaneously if it’s stored in large quantities, not refrigerated, or if the film deteriorates too far. (Thankfully, this never happened at the Bentley! But is has–on purpose–at places like this Nitrate Film Vault Test and–unfortunately on accident–at places like MGM and NARA.) It can also catch fire if multiple negatives are stored close together and rub against each other, which is why you saw that even in the collection AS RECEIVED by Ivory individual negatives or strips of them were stored in individual sleeves, to prevent that rubbing.

About 10% of the negatives in this collection are made of nitrate film… something we didn’t know before starting the digitization process, in part because nitrate film can be hard to distinguish from other types of film.

(And you can imagine our EXCITEMENT when we found out this collection contained nitrate… it changed the scope of the project entirely.) People ask all the time how much it will cost us to digitize something, or how long it will take, and this is a good lesson, I think, in how you can’t really predict any of that until you actually get into a collection and take a look.

And this, BTW, was ANOTHER fun adventure: besides finding a vendor that in addition to everything I already listed was ALSO willing to work with nitrate film–most don’t want to touch it with a ten foot pole!–we had to figure out a way to get it to them. In Massachusetts. And it turns out you can’t just send hazardous, combustible material through UPS, which is what we normally do. It also turns out that AMAZINGLY, nobody at this big and beautiful but also incredibly decentralized and bureaucratic university seems to know how to deal with this stuff.

Not Just a Copy

So, a year and half and $110,000 later–not including the staff time and student workers it took us to prepare these photo negatives for digitization, which was substantial–we are on the cusp of a collection of 10,000 original negatives AND… 10,000 digital surrogates of those negatives. And not JUST copies, but an improved, potentially-more-accessible-in-more-ways-and-to-more-people resource.

Some of the things that make this version potentially better:

- First and foremost, we get “not just A copy,” but a HIGH QUALITY digital copy of the original, one that we can also archive and preserve for future generations, so long as we also apply the same preservation quality storage to the digital as we do to the physical. And please ask me about this later because digitization != digital preservation and I LOVE talking about digital preservation.

- Since we can now use the digital surrogates for access, we can keep the originals safe. We can keep them in our freezer and even fewer people than before will ever have to touch them: they are much less likely to deteriorate over time if we ever needed to go back to the originals.

And because of all this:

- A less likely to spontaneously combust resource. A less vinegary-smelling resource.

- A resource you don’t need a specialized viewer to access; in fact all you need is your computer or phone.

- One you don’t have to physically visit the Bentley to take advantage of.

- One you can blow up and zoom in on and even do new kinds of research with.

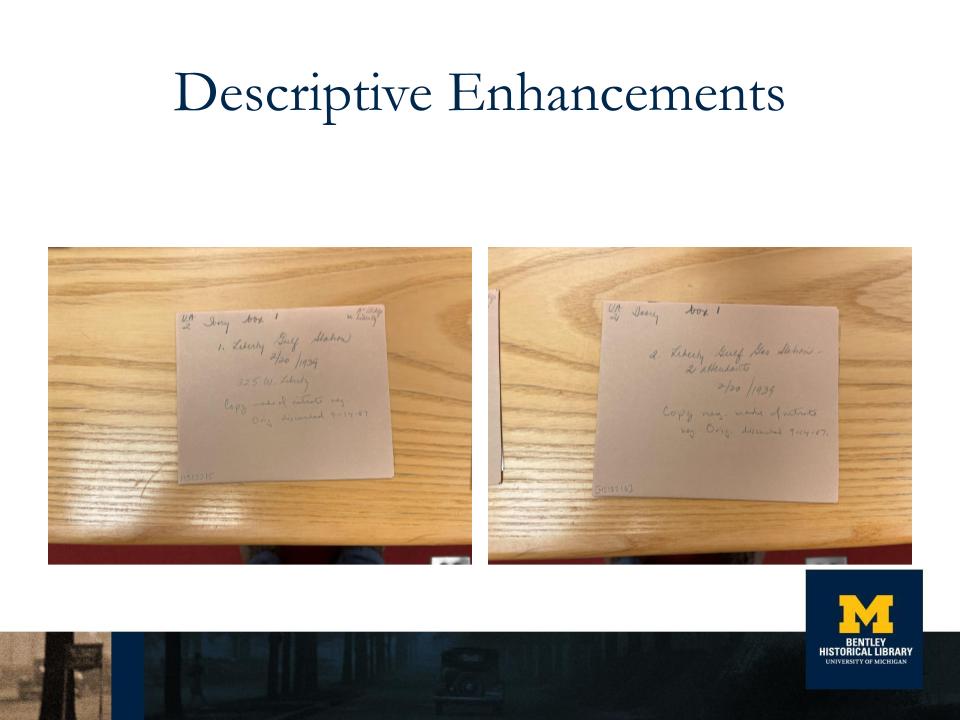

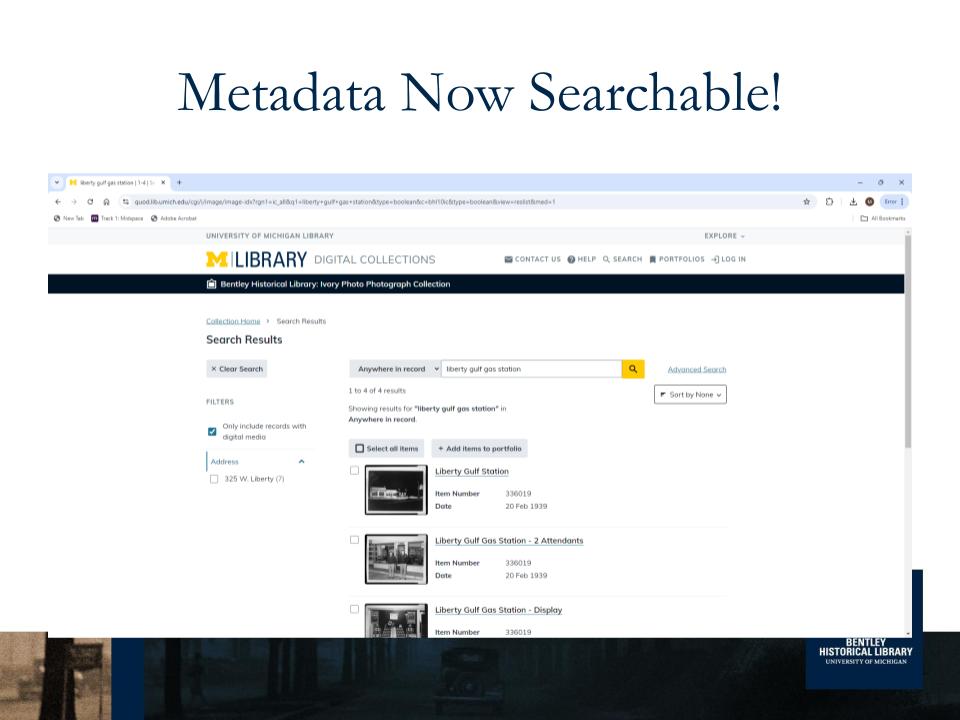

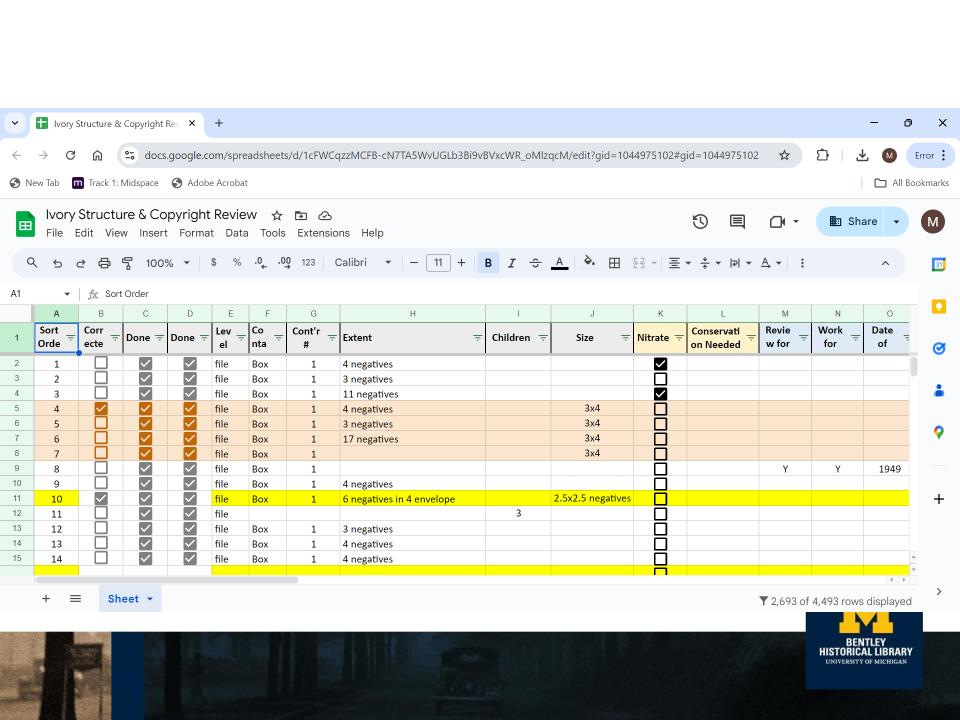

I also really want to draw attention to the descriptive enhancements we did along the way. While these aren’t strictly related to the “digitization” process, they are important and lead to an much improved resource. Essentially, we asked the vendor to transcribe Ivory’s original labels… ones he had handwritten on the sleeves the negatives were stored in…. so that the context of the creation of the images was knowable. These descriptions usually contained important information like the subject of the photo, the date it was taken, its number in sequence (if there were multiple photos), address, name of business, who he was working for at the time, etc. So it’s good stuff! Especially because the collection was originally organized by size of negative (what fit in what box) and not so much by content.

Even after the transcription, we had to massage the data a bit and create a basic structure for it, but now we have a collection that’s not just viewable but fully searchable as well!

So, yeah, incredible. Kind of. This kind of resource is only as useful as the number of people who can use it. Ultimately, we knew that we wanted this material available beyond our Reading Room. I’ve been teasing you with the final product, but having this kind of online resource was far from a forgone conclusion.

Getting the Stuff Online

And that’s because the “making the collection available online” part, it turns out, is ALSO not particularly straightforward. And it’s important here to recognize the HUGE difference between: 1) an INDIVIDUAL researcher traveling to the Bentley to look at INDIVIDUAL records from a collection within the confines of our Reading Room; and 2) us digitizing EVERY record in that collection and putting it online so that ALL researchers can access the material, ANYTIME and ANYWHERE.

It’s Not JUST Technology

And this is where I want to introduce you to my colleague, Matt. (See what I mean about resolution?) Matt is our Lead Archivist for Digital Imaging and Infrastructure, and was the project lead for this project.

(And I feel like I have to say, here, Matt is great. We interviewed him for this talk. And, yes, he is known at the Bentley for his technical expertise and all things digitization, but ALSO for the joy he brings to the workplace because he is who he is: his love for wildlife–turkeys and deer and groundhogs, especially, because we kind of have a problem with those at the Bentley–homemade treats he brings every year around Halloween, his numerous adventures trying to catch the Northern Lights, the fact that on the side he’s an EMT, and so much more. He’s really a very affable guy.)

Anyway!!!

Everyone at the Bentley got into this business because we love archives, and believe in our larger mission of serving the community by preserving knowledge and culture and the human experience in all its forms for generations to come. Matt, though, and me, and actually everyone on the Curation Team–the ones that process collections and conserve them and digitize them–WE got into this business because we share a love for archives AND technology.

And providing preservation and enhanced access to our materials via methods like digitization is one of the most important and exciting ways that we fulfill this mission. And, yes, a lot of doing that is about technology. The technology of photography, negatives, digitization, metadata, online digital repositories, image APIs, etc., even things like good project management.

But! It’s also the part of our work that can get us into the most LEGAL trouble. And as I’m sure you know, when it comes to the law, tech will not save us.

I’m talking here about copyright infringement (and its cousin, fair use), and how hard it is to keep everybody–photographers, like Ivory, who have an artistic and, let’s be honest, a business/commercial interest in who has access to their material, scholars and the public like you who want to access it, archivists like us who want to give you access, and lawyers at the University and elsewhere who are trying to keep everybody happy–calm and satisfied when doing projects like this.

And yeah, there’s a lot to copyright law. More than I can get into tonight, especially when you’re talking about getting digitized material out there for the world to see. And a lot, actually, that is still being worked out and argued over in court, which is kind of by design.

But the short of it is that because of copyright, you really CAN’T JUST digitize everything and put it online. You have to build and ultimately make what’s called a “fair use case,” and a STRONG one at that. Unless you want to get sued, a lesson the University learned the hard way over the years because it is progressive… some might even say cavalier and… it got sued for doing just this kind of thing. In a big way. (There’s a previous Making MI lecture on this topic that you should definitely check out.)

It’s ALL Yellow Lights

All of this is to say that when Matt and I sat down to review this collection, we understood the technology. We’re also copyright “first responders” of a sort, and had a basic sense of what the absolute RED FLAGS are when it comes to putting digitized material online (think ANYTHING with contemporary recorded music… Taylor Swift anyone?), and what the absolute GREEN FLAGS are (think anything REALLY old, like Civil War letters, so old that anybody the material is by or about is long since dead and gone).

The problem with Ivory Photo, and what made it really challenging for us beyond the technology, is that it is FULL of YELLOW FLAGS. Like, nothing but yellow flags. The timeframe Ivory worked in meant that the ownership of copyright of the images belonged (and still belongs) to whoever Ivory did the work for. Sometimes that was the University (in which case we already own the copyright, so no problem there), but other times it was for local businesses, some of which are now defunct, national businesses like AAA, local organizations like churches or, you know, just Jane or Joe Schmo who hired him for a particular job. There are literally HUNDREDS of copyright owners in the collection.

We also knew that: 1) there were a lot of photos (10,000!)–TOO MANY to review on an item-level, especially because there was an ACTUAL DEADLINE of Ann Arbor’s birthday we had to be mindful of; 2) Ivory only SOMETIMES indicated who he was doing work for on those sleeves–because I’m sure he didn’t anticipate THIS particular use case; and 3) in any case experience and studies on this subject show that trying to track down copyright holders in similar circumstances does not yield productive results. People are hard to find, and even when you can find them, they don’t respond when you reach out.

So, we had to figure out what to do. We reached out to the university’s wonderful copyright lawyer, Jack Bernard, for advice. He encouraged us to do a selective copyright review of the collection. It’s actually not the kind of detail we’d go into for something like this, because we generally stick to GREEN FLAG collections–or, let’s be honest, GREEN-ISH FLAG collections–when it comes to our digitization efforts of entire collections that we intend to later put online. But because this is a photo collection, and because of the time period, we knew that there was a bit more risk involved. Even though we suspected it would yield very little (and that’s ultimately what happened), we thought it was wise advice as due diligence. So we followed it.

The Fair Use Case

This analysis, coupled with our standard takedown policy, which states that we’ll work with you if you think your copyright or privacy is violated by us putting something online, ultimately led to our fair use-over-copyright infringement case, which is what libraries and archives use when doing digitization projects to justify and record their decision to make that digitized collection available online. It’s a kind of CYA argument. It leans heavily on the fact that:

- we’re doing this strictly for educational as opposed to commercial purposes; and

- the effect of this use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work (which is what copyright is really about, after all) is essentially none.

It also acknowledges that yes, we’re digitizing the whole collection as opposed to a “highlight real”–which is the equivalent of digitizing a whole book and sharing that rather than, say, JUST a chapter of it. To be clear, this is generally frowned upon. We HONESTLY felt, though, that we HAD to because of the value of the collection as a CORPUS of work that documents not just Ann Arbor history, but also changes in photography and film technology, over time and from a consistent perspective.

That said, we ARE taking a measured and deliberate and ultimately INCREMENTAL approach to putting it online. Starting with the stuff we’re least worried about when it comes to copyright, which also happens to be the local stuff, and going from there. And, you know, this is where our select review and takedown policy also come in. Nobody is being cavalier.

In the end, we felt like we had a pretty strong case for fair use, and so we proceeded! And we worked with our friends at U-M Library to get it online.

And Here We Are Today

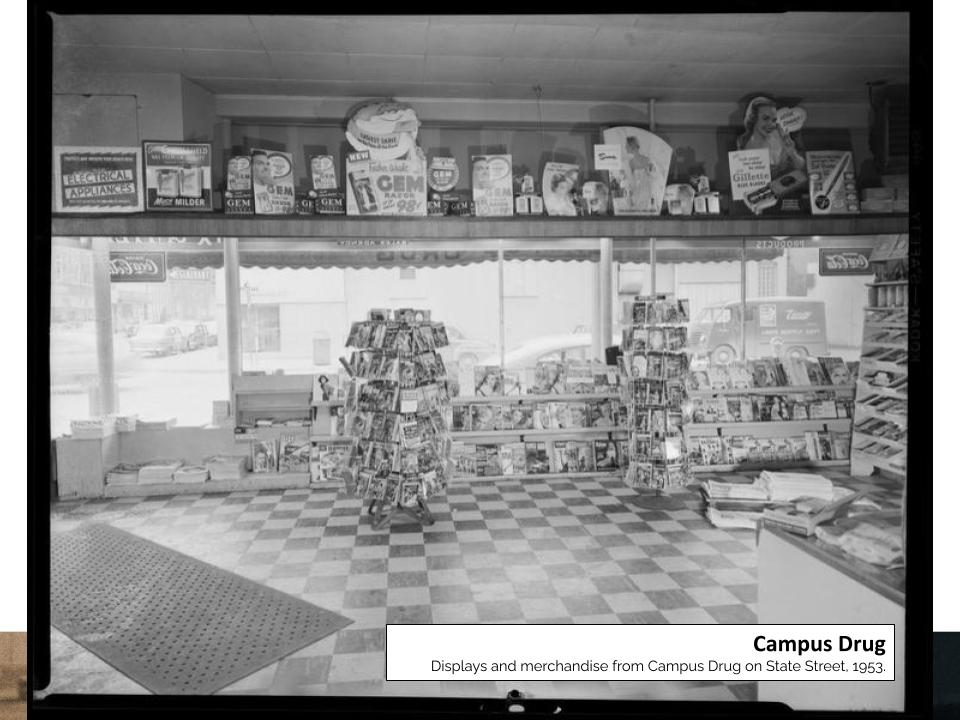

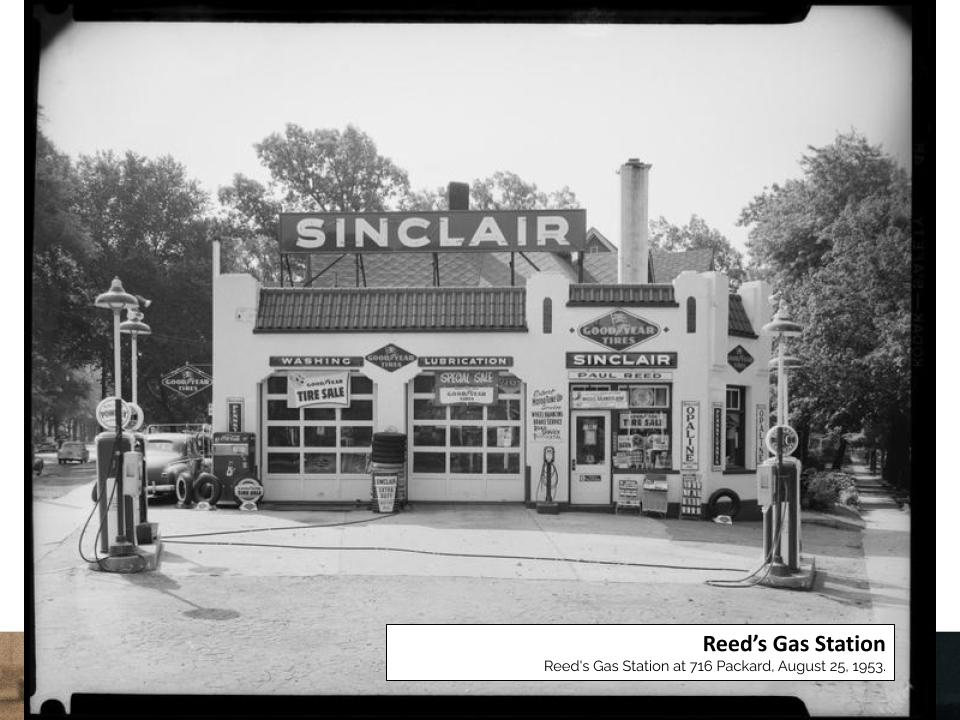

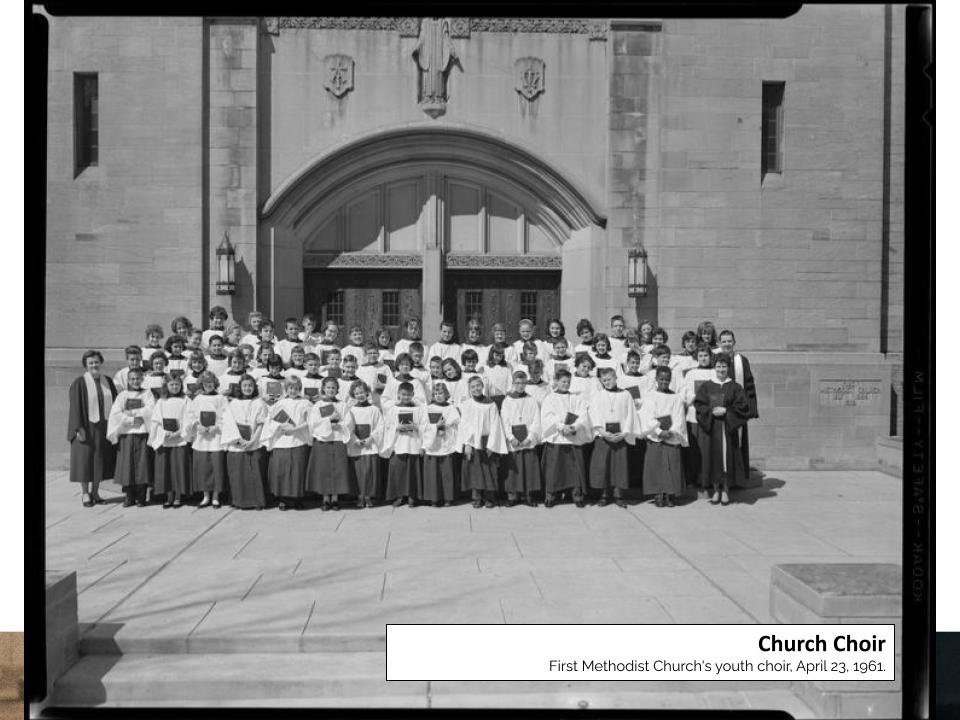

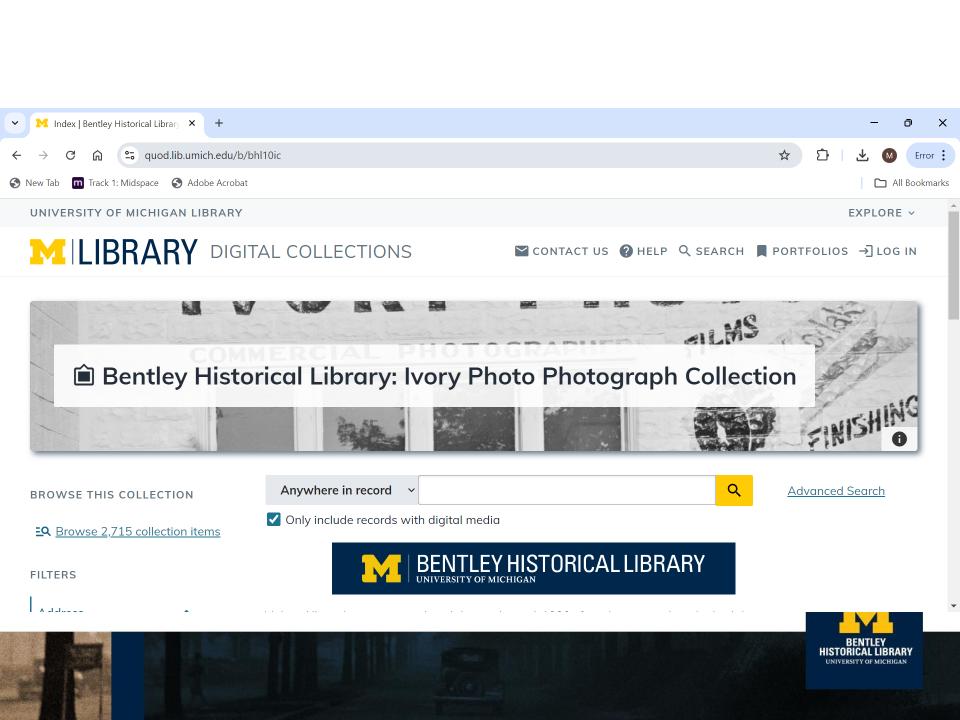

And here we are today. If you go and visit the site, you’ll see that 2,715 of these images–the ones related to Ann Arbor and the University of MI–are available online, fully searchable, shareable, downloadable, blow up-able, zoom in-able. Happy Birthday, Ann Arbor!

Meanwhile, we’re also monitoring the feedback we get from this portion of the collection being online–including any concerns about copyright infringements… so far none–and frantically working to QC the other 7,285 (or so) images we recently got back from the vendor to get those online, as well.

Categories: talks